I recently learned a new term to describe a forest ecosystem. The water district of Oak Bluffs, a town on the northern tip of Martha’s Vineyard, proposed going “green” at the site of their pumps and wells. They would add solar panels to the site to make electricity to power the pumps that supply the town center with drinking water. The plan was shot down by the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, the regional planning council, on the grounds the project would entail entirely clearing between 6 and 10 acres of the site to build the frames that hold the panels. David R. Foster, the director of Harvard Forest, which is in central Massachusetts, happens to live in West Tisbury, which is on the island. He told the commission that “ancient woodlands” would be destroyed should the project go forward.

“Ancient woodlands” was initially a baffling term to me (although I found it is used routinely in the United Kingdom). The forests of the island date from the 19th century, generally speaking. As is the case for much of New England, particularly the southern portion, the land was almost entirely cleared for agriculture, pasturage, and for firewood, between the 17th and the 19th centuries.

Martha’s Vineyard was settled by Europeans after 1641 when Thomas Mayhew purchased the island from the Earl of Sterling and Sir Ferdinando Gorges. The Wampanoag had (and have) inhabited the place since you could walk to it on dry land after the last Ice Age. Like other coastal tribes they burned the land to keep it clear for agriculture and for hunting. Parts of the Vineyard, the portion that is glacial outwash plain, was also open heathland (home to the heath hen), perhaps even before the Wampanoag began burning it systematically, and not forest at all. But in a March 2016 letter (included in an August 2016 letter) to the commission Foster, the author of a monograph about the island’s forests, stated that 40 percent of the Vineyard’s woodlands had come through the historical clearances intact, and the Oak Bluffs water district site was within the largest remaining tract.

Foster explained that an ancient forest is not really about the age of the trees; it is about the age of the ecosystem. The parcel owned by the Oak Bluffs water district turned out to be a piece of land that had never been tilled. The soil architecture and its attendant microbial and invertebrate ecosystems had never been disturbed. It therefore supports a sub-aerial floral communities that is similarly continuous. These are not majestic, old growth forests with towering trees and haunted silences. Instead it is a scrubby-looking tract populated by several species of oak in the canopy and a sub-canopy somewhat oversubscribed with ericads. There is, of course, more to it than that, but that is definitely what meets the eye of the casual observer.

This is an ecosystem distinct from an old-growth forest. Old-growth as defined by non-foresters includes the idea that the mature trees in a stand have never been felled by a lumbering operation. Old-growth forests presumably share a lot of sub-surface characteristics with ancient forests, but the sub-aerial expression is quite different. No one claimed that the trees at the water district site were hundreds of years old, but Foster said that the ecosystem had been undisturbed by human activity for millennia:

These ancient woods are particularly important because their soils are intact, their vegetation has continuity on the landscape going back thousands of years, the resprouting trees on these sites are many hundreds of years old, and the habitat that they provide is globally rare and valuable to many unusual as well as common species. (excerpted from Foster’s March 6 letter)

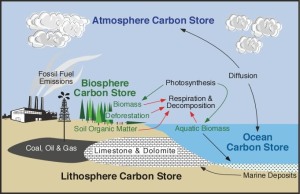

Foster and other opponents argued that the forest was doing its job sequestering carbon and keeping it out of the atmosphere, and it was “counterintuitive” to remove it and build solar panels, which were after all meant to contribute to the switch away from carbon-based fuels. Although there is a difference between the short-term storage of carbon in a forest and long-term in a coal deposit, we have little hope of actively creating or maintaining long-term storage (although Freeman Dyson and some others do feel otherwise) and maintaining our ancient woodlands where we still have them seems prudent. Especially, as Foster points out, there are so many roof tops, gravel pits and other disturbed sites where solar panels can be erected.

Clear and thorough as usual