Nearly anywhere you go in the United States you will find oak trees. They are often large and common, so they can often contribute significantly to the look and feel of a place. The effect reaches consciousness if you are a plant nerd. During the year I lived on the Central Coast of California, I was somewhat distracted by the fact that several species of oak did not lose their leaves in the winter. And what could be more different than the spreading, moss-draped live oaks of the Southeast versus the upright, austere red and black oaks of the Northeast?

I have been reading that before the European settlement period Martha’s Vineyard was not as heavily dominated by oak forest as it is now. (When I repeated this statement to a naturalist in the employee of The Nature Conservancy, she contested it. And David Foster’s book A Meeting of Land and Sea indicates that it is a lot more complicated than that.) Supposedly, the up-island portion of Martha’s Vineyard, which is higher, rockier, and less sandy than down-island, was once more of a northern hardwoods assemblage, characterized by beech, maple (mostly red), black tupelo (locally called beetlebung).

But clearing of the forests for sheep raising between the 17th and 19th centuries led to erosion of organic-rich top soil, so when animal husbandry and farming faded and the island became a site for second homes, the forest that returned was one more adapted to drier sites with more mineral-dominated soils. In the Northeast, this tends to be the preferred habitat of the post oak (Quercus stellata).

I am not familiar with this species. It is a common oak in the South and southern Midwest, but is confined to marginal areas in the Northeast: sand barrens and rocky ledges. In Massachusetts it is found in Bristol and Barnstable counties on the mainland (Buzzards Bay and Cape Cod) and on the Islands. This represents the northeastern corner of its range; it extends southward along the Connecticut coast and on Long Island.

It is a famously slow-growing species and the wood is rot-resistant. It gets its common name from its sturdiness as a component of fence construction. It often takes a spreading form, the branches assuming sinuous shapes, and generally reaches the height of 50 feet, although it can grow to twice that height in a suitable location.

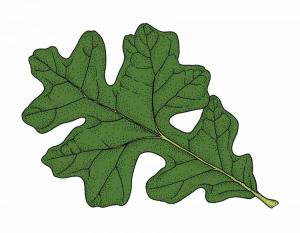

It is in the white oak group, so the lobes of the leaves are rounded and without the terminal ‘pins’. The acorns mature in one year and are sweet tasting. White oaks also readily hybridize among species, making identifying characters somewhat variable from tree to tree. The post oak usually has leaves that are said to resemble a Maltese cross; they are narrow at the base and have three broad, squared off lobes at the distal end. The underside of the leaves are covered with fine hairs called trichomes. In the post oak these have a star-shaped cross-section, hence the trivial name stellata.

Oak leaves are poisonous to sheep and goats, so it seems odd that they are so common on this island, where sheep raising was such an important part of the economy. Apparently the sheep won’t each the leaves if there is enough grass around. Sheep are consummate grazers, even less likely to browse than cattle or horses.

When you wander the conservation lands of Martha’s Vineyard, you frequently encounter stone walls that now wend their way through the woods, but once delimited the boundaries of sheep meadows. Amid the younger trees you find larger, spreading trees — they are occasionally post oaks — that must have been there to provide shade for sheep and shepherd. I still have some questions about whether eating oak leaves was a concern, but it is a pleasant picture to conjure.